Hammer’s Dracula: Finally, Someone Got It Right

Nosferatu was a hopeless tragedy. Universal’s Dracula was a bourgeois drama. What could Terence Fisher’s Dracula (1958) do to outdo them both?

Now that we have seen the two most iconic movie adaptations of Dracula (Murnau’s symphony of horror Nosferatu, and Tod Browning’s Universal production Dracula starring Bela Lugosi), we can finally play with the big boys.

Imagine, if you will, a vampire movie where Grand Moff Tarkin as a supercatholic demon hunter fights the undead descendant of Charlemagne.

Now, imagine it with actual blood on-screen.

Oh yes, this is about to rock your world.

After their immense commercial success in 1931, Universal Studios produced a wave of cultural icons, in the forms of monster movies: from Frankenstein to The Invisible Man to Dr. Jekyll and Mr Hyde to The Wolf-Man, the studio pumped them out in rapid fire to capture forever the imagination of generations, creating in the process what I would not hesitate to call the very first cinematic universe.

But, as the years rolled by, these carefully fashioned masterpieces became old-fashioned, as is the curse of all cinematic universes (though some experience it quicker than others, isn’t that right Zack Snyder?). Soon, Dracula, the Mummy and other iconic creatures of horror took a turn for the ironic and comedic as early as 1948, in Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein.

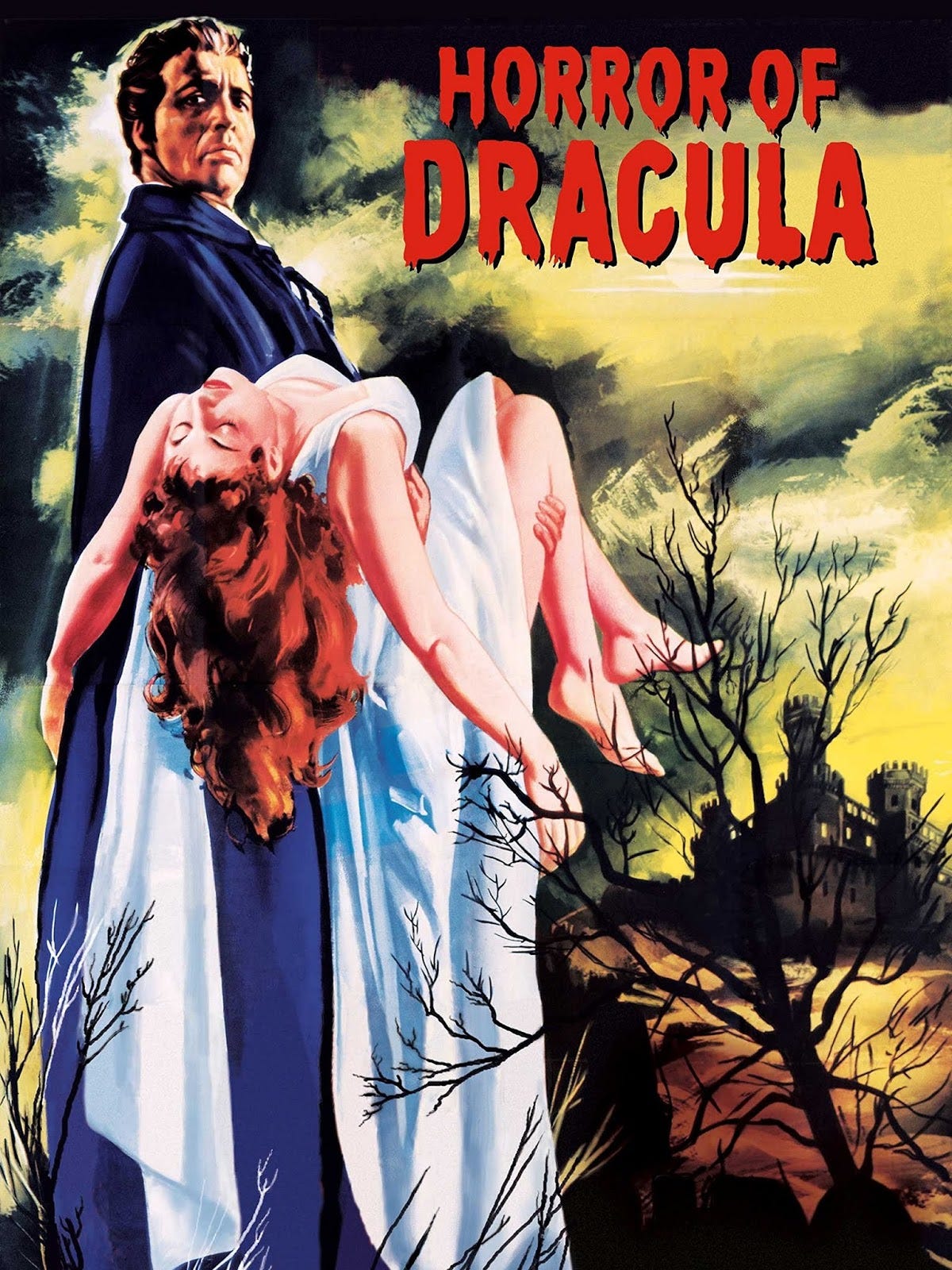

So, when Hammer Productions, a small English film company, decided to create their own version of the New Prometheus in the late 1950s, you and I would be forgiven for thinking the enterprise doomed to fail.

And yet, you and I (as often) would be wrong: for as soon as The Curse of Frankenstein hit the screens in May 1957, it rekindled the public’s passion for this new old-fashioned horror.

The recipe was simple, but effective: take a Universal Horror classic, twist the story around to keep things moving, add in bright colors including a butt-load of vividly red blood, turn the sexual undertones into overtones, and get the classiest British actors you can find to play the main roles.

This was the winning strategy that turned Hammer Productions into a household name, with its new juicier twists on Universal’s classics: namely The Curse of Frankenstein (1957), The Mummy (1959) and, of course, Dracula (1958).

And after a re-watch, I must say this Dracula has a bite that the others never had. But let’s talk about why.

Blood and boobs: remember when this was considered shocking?

This first point may seem a bit crude and surface-level: what’s so interesting about this? Previous adaptations implied the acts of vampirism without ever showing it, and it was just as effective. So why should seeing Dracula in action be a game-changer, instead of a simple loss of subtlety in storytelling?

Well, first of all, something the original novel does wonderfully well is suggest images, particularly images of horror. And film being a visual medium, I found both early adaptations severely lacking in their depictions (through no fault of their own, since they were limited in both budget and elbow-room).

But here, after the resounding success of The Curse of Frankenstein as a proof-of-concept, Hammer’s Dracula goes in a more graphic but still restrained portrayal of the classic vampire tale. You can finally see something closer to Stoker’s vision:

“The Count turned his face, and the hellish look that I had heard described seemed to leap into it. His eyes flamed red with devilish passion; the great nostrils of the white aquiline nose opened wide and quivered at the edge; and the white sharp teeth, behind the full lips of the blood-dripping mouth, champed together like those of a wile beast.” (Dracula, Chapter 21)

Some scenes, now restored, were even cut from the original release.

Of course, we are far from The Shining’s elevator scene: at its worst, you’ll get a little blood spurting out as Van Helsing drives a stake in a she-vamp’s heart. The rest of the time, it’ll merely look like Chris Lee ate his fries with ketchup that day. But the fact we can actually see it (and in color, no less) creates far more striking visuals.

That is not to say this iteration of Dracula is not deeply tributary to its famed predecessors: Bela Lugosi’s shadow still looms over this new Count, who still sports a tasteful black cape and elegant slicked back hair. And the fact he traded his tuxedo for an all-black suit calls back even so far as Count Orlok (as does this stair-climbing scene).

But a key change here remains to be discussed: this is the first time Dracula is a stud.

In stark contrast with Lugosi’s sophisticated exoticism or Orlok’s primal impulses, Christopher Lee’s Dracula plays up the seductive side of the character: women seem to immediately fall for him, and in fact none of them are even shown to resist his allure at any point (and yes, alas, we will talk about this in a bit).

Max Schreck played an impulse given an ugly, bestial face. Lugosi played a vile monster hiding behind a gentleman’s appearance. But Lee’s Dracula is a monster through and through, with hardly any façade to hide behind. I’d go as far as to call him an incubus (as the freshly-turned vampire ladies display succubus qualities, yowza yowza), though he is a lot more than this.

This Dracula is also a feral beast, capable of great physical violence, grappling and throwing his opponents away like straw. Something which, again, we have not seen in any previous adaptation yet.

Although this movie is a bit licentious with its tastes for sex and gore, I believe it also participates in creating something which the other films never reached as completely: a palpable battle between good and evil.

Finally, a real battle between Good and Evil

Now this might be a bit harsh: after all, Ellen’s sacrifice to save her husband and her town from the Nosferatu, or Universal’s Van Helsing setting out to destroy the dreaded vampire, are both clear examples of good striving against the blood-sucking evil.

But there are two key points that make Hammer’s version stand out on this:

1) When we see something brutal or dangerously alluring in this movie, it always serves a point: for example, the death of Dracula’s bride, showing the first on-screen vampire-staking in a manor movie adaptation, gives us a potent cocktail of shock, fear and horror, as the blood spurts out, the woman shrieks, and her bountiful body turns into an old hag’s corpse. There is no glorification of vampirism, but a clear portrayal of the bare violence that lurks behind their deceitful allure.

And Dracula is even strangely monogamous: he never has more than one bride at a time.

In this light, I believe even the violence and not-so-subtle sexual content serve a cathartic purpose: beyond the shocking spectacle (which no doubt served the company’s interests), there is a clear moral backbone that serves as an opposite to the monster, and which gives him his “bite”. A line is drawn between light and darkness, between the brutal lust of Dracula and the cool resolve of Van Helsing. Evil exerts its influence, drawing us in and scaring us away, attracting and repelling, until it finds its eventual defeat, perhaps leaving us with the courage and resolve to face our own demons. In this sense, the very brutality decried by the more conservative critics of the time may serve to tilt the movie’s own moral compass back in the right direction.

2) The characters display traits we rarely had time to see in previous movies: Dracula preys on young Lucy not because of mere attraction, but to get revenge over her fiancé for trying to kill him. Later he preys on Mina for similar reasons. He is petty, possessive (he can’t even let his own bride drink a little blood from Johnathan Harker), holds grudges even beyond the grave, and flees when faced with determined enemies.

In contrast, Abraham Van Helsing (portrayed wonderfully by Peter Cushing) is single-minded, rational, cold-blooded against his enemies yet warm and caring to the people around him.

“You look like a teddy-bear, now.” - Fierce vampire-hunter Abraham Van Helsing

His use of a phonograph to record his study on the vampire (a nice nod to Dr. Seward’s audio journal from Stoker’s novel) reveals a methodical man, whose use of garlic and crucifixes has less to do with superstition than with repeated observation. This purity of mind is also exemplified in the fact that he never speaks to the vampires, which reminds one of Catholic priests who are to never respond to the Devil’s taunts during an exorcism.

It’s a clear U-turn from the previous Van Helsing, whose dialogue with Dracula was the pinnacle of the Universal movie. Although comparing these two is quite unfitting, as we will see in a few paragraphs…

If this is not the first time we got a Dracula movie where good and evil were set against one another, I believe it is the first time we got to see an actual battle between the two. For this movie’s plot, though not airtight, shows a clearer progression in the stakes, a constant confrontation of wits and fists that culminates in a final duel.

For this movie, at last, is what any other Dracula movie should also be: an adventure.

Finally, a real adventure movie:

Rewatching this movie last Saturday night, in the cozy shadows of my room, made me realize how much I had missed this particular side of Stoker’s story. But it’s true that, under the horror aesthetic, it is an adventure story.

You have a young loving couple put in mortal danger, a band of good friends vowing eternal fidelity, an old mentor chaperoning them on their way to victory; you get short bursts of gothic horror, extended scenes of strategy and deduction, close encounters and action scenes, long chases across land and sea… There are all the ingredients of an adventure movie!

And, even though the story is dramatically shortened, this film still delivers a solid punch.

Not only do we get action scenes, including a chase scene on coaches (the first of so many for Hammer), but the general flow of the movie is tightly connected by the plot: every scene brings something new to the table, either giving a little bit of information or directly foreshadowing a scene of horror.

Of course, one could not achieve as much as the book in under an hour and a half: so the movie’s script had to make severe choices:

1) The story takes place in a European handkerchief: all of it happens between the village of Klausenburg (the closest equivalent of which being Cluj-Napoca, Romania) and the city of Karlstadt (which may correspond to Karlstadt am Main, Bavaria). And considering our heroes manage to travel all the way from one to the other in less than a night, it would seem they are even closer than the two real cities they were inspired by.

This is a dramatic change compared to Stoker’s continent-spanning epic, but it gives the story a much-needed dose of nerve, and allows for a quicker resolution.

2) The characters are severely changed, and compressed together: here, Dracula kills Johnathan Harker and takes a liking to his fiancée Lucy, Arthur Holmwood’s sister, while Arthur himself is married to Mina; and Van Helsing helps them, as he and Harker were vampire hunters. Needless to say this diverts hugely from the novel, which showed a rich array of characters, each with their own specific traits and habits, exhibited especially when we read their own words as they relate the story.

3) All the fluff is cut: there is no slow discovery of the vampire’s abilities, no inquiries across London on the possible locations of all of Dracula’s earth-boxes, no long scenes of our heroes planning and comforting each other… This leads to a much faster-paced story, while keeping far more of the more adventurous side of the novel than what we get in Universal’s or Nosferatu.

And yet, with all these changes, how could this movie qualify as a better adaptation?

Well, I still believe it does, thanks to a little something I have called:

Narrative reverse-engineering

Now, let’s go back to 1958: vampires are known to the public by now, even though they have vanished into the background of pop culture. So how do you do another Dracula that keeps the same bite as the original?

Simple: by subverting expectations.

No, not like that.

Let’s think about this: as we see Johnathan Harker driving up to Castle Dracula, what are we to expect? That through his eyes, we will progressively learn Dracula’s true nature, see him fall victim to his bite and get left behind for his brides to feed upon while he goes gallivanting in the big city.

So, we want to gain some runtime, create suspense, and reveal Dracula’s vampiric nature, through Johnathan Harker as a vehicle for the audience.

But the audience knows Dracula is a vampire. They know about garlic and crucifixes, “children of the night” and plastic bats fluttering through the windows. So how do we freshen up this plotline and give them something new?

The solution is simple: Johnathan Harker knows About Dracula.

Better than that, he’s there to do what the audience would want to: to stake the vampire and his brood through the heart and rid the world of their evil.

Now we’ve successfully flipped the story upside down, where Harker lies his way into Dracula’s trust instead of the other way around. But right as you may start to get comfortable, the bride comes along. She begs Harker for help, she can’t be that bad… Except she is.

And Dracula bursts in, with blood dripping from his fangs: he doesn’t like to share his future meal.

And later, as Harker dies at Dracula’s hand, we the audience are left without a guide: we have been successfully subverted, and will welcome our new hero in the form of Van Helsing.

And to make things easier, we establish a small group of characters:

Lucy, the object of Dracula’s revenge over Harker killing his bride: she’s there to fall under the vampire’s spell until she becomes a vampire herself. She’s there to show Dracula’s power, and how thoroughly he can turn a normal human being into a monster.

Arthur Holmwood, who serves as the skeptic, and through whom we see the struggle of the normal man against the unsuspected irruption of the supernatural in the very heart of his life. He also becomes the aid of Van Helsing, helping him to figure out Dracula’s plans and how to foil them.

And Van Helsing, who “carried out research for some of the greatest authorities in Europe” on the subject of vampires. He can quickly establish the canon strengths and limitations of this Dracula, mixing and matching multiple ideas from previous movies, so that we can know what to expect.

In doing so, we have the key elements of the original novel, though changed and turned upside down only to be brought right side up again. The story ends in a chase scene to kill Dracula before Mina is turned forever into a vampire. And only through the actions of both Arthur and Van Helsing can we finally reach victory over the bloodsucker.

A few significant misses: unfaithful to the letter, but true to the spirit

Of course, this method has its drawbacks, and some characters suffer heavily for it:

First of all: we get no Mina. There’s a character called Mina, but she’s an entirely different character, with none of the purity, attentiveness, strength of character and sheer brains of the original. It’s a tragic misstep, though explainable by the structure of the story, and I wish they could have given her an actual role, instead of being yet another of Dracula’s victims, there to be rescued by the other characters.

And sadly, as mentioned before, female characters are all immediately under Dracula’s spell, making them incapable of helping Van Helsing and Arthur, as they are willing accomplices of the vampire.

In the same idea, Van Helsing still has to do most of the work: unlike the novel, which is a clear example of team-effort defeating impossible odds, this movie pretty much puts Van Helsing on a pedestal. Not an undue position, mind you, but one which takes the story further away from the original.

And yet, as far as themes, visuals, and overall plot are concerned, Hammer’s Dracula remains faithful to Stoker’s work: if not to the letter, then to its spirit.

And as we will see next time, there are ways to adapt Stoker’s novel scene by scene, and still miss the entire point by a couple lightyears.

See you next week, as I prepare to suffer.