OooooooooOOOOOOOooOoOoOoOoooooh…

Since our American overlords (whom we love oh so very much, Mt 5, 44) have decided October would be the spookiest season of them all, then it seems only fitting that we should talk about one of the most famous monsters of the last century; the murderous, shape-shifting, blood-drinking, womanizing, infernal creature in the guise of a human, whose life is nothing but an endless string of hellish horrors...

No, not that Hollywood guy.

No, not that one politician either.

…

Alright, in order to not spend the rest of the month plunging into the depths of real-life depravity, let’s talk about Dracula, movies, and why they suck and the book is better.

As I have discussed previously, the Count is the product of an odd crossing between the modern and pre-modern world: as urbanization, industrialization and positivist scientism reached their peak, the last wake of neoromanticism was already on its way out when Bram Stoker published his rightfully world-renowned novel.

And since it is so indelibly associated with Victorian imagery (from fine dresses, top-hats and horse-driven coaches to dark shapes shifting through the mist-laden streets of London), it seems vertiginous to think that, less than 20 years after the novel’s publication, both the modern and old world would be plunged into the boiling depths of war on a never-before seen scale.

In comes Nosferatu.

And let’s rip off the band-aid right now: yes, Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau’s Nosferatu is a progressive, even deconstructive movie, in more ways than one. Well, sort of, it’s a bit of a mix…

If you haven’t seen it, now is the season. There’s a restored version with music right here.

All caught up? Good! Now, let’s get to the positives first.

A dark, romantic dream

One of the coolest narrative elements in Nosferatu is that it presents itself as a “Chronicle of the Great Death”: the movie is presented (at least partially) as a testimony of a real, terrifying event that has scarred the humble city of Wisborg.

In this way, it emulates Stoker’s epistolary novel, especially since they add in a letter from Hutter (Johnathan Harker’s non-union German equivalent) to his wife Ellen (the poor man’s Mina Harker), as well as newspaper clips, and the ship’s journal of the Empusa (the equivalent of the Demeter in the novel).

It hits the same sort of narrative flow, while relying on visual storytelling (which, by its very nature, is less appropriate for an epistolary format). An achievement not even Coppola could outmatch

And boy do I have things to say about that one. But we must wait… For now…

What’s more, the movie added new elements to the Dracula mythos, which enrich the setting and the dark influence of the antagonist: the populace attributing the death of the vampire’s victims to a mysterious “plague”, the many references to esotericism (like Orlok being born of “Belial’s seed”, connecting him to the wider world of the Nephilim), and even the unnatural look of the creature itself.

And speaking of visuals, they still hit the spot over a century later. Murnau shows a brilliant use of shadow and light, especially effective in black-and-white pictures. And some shots, like Orlok rising from his coffin, the shadows of his claws spreading over his victims, or that chillingly still shot of him drinking Ellen’s blood, deserve their iconic status.

And they add to that one element which I find very compelling: this movie feels like a dream. Or rather it uses the logic of dreams to a great extent.

For instance, this is the only Dracula adaptation I’ve seen that shows the vampire as an ethereal being, something you cannot always grab or stab. Contrary to Universal’s, or even Hammer’s Dracula, Orlok can not only change shape (to the point that villagers nearby call him a werewolf), but also vanish into thin air, or show himself as a ghostly apparition.

Other than that, his ability to open doors at a distance, the rigid, inhuman way he walks, the invisible influence he exerts over Knock or Ellen across hundreds of miles of distance, all make it feel like a living nightmare.

Doesn’t it make even more sense now that the story – and the monster – should find their end with the rise of the sun?

But enough about the positives. We want blood!

The conspiracy of the Old against the Young

One of the key changes in Murnau’s movie compared to Stoker’s novel is the way it treats its younger and older characters.

The novel rightfully pays more attention to its younger, proactive characters like Quincey Morris, Lucy Westenra, Arthur Holmwood or Mina and Johnathan Harker (and yes, we’ll talk about these two in a minute).

Yet the older characters, even as they remain in the background, are largely positive figures: we hear nothing bad about Arthur’s father Lord Godalming, Lucy’s mother is excessively gentle, and Harker’s employer Mr. Hawkins, has a heart of gold, and does his best to ensure Johnathan and Mina’s future as best he can.

And do I even need to mention Dr. Abraham Van Helsing, the paragon of mentors, vampire-hunter extraordinaire, who is as knowledgeable on biology as he is on the supernatural?

Then again, if you want to read more about it…

Now let’s contrast with Nosferatu.

Firstly, Murnau smashed together two entirely opposite characters, the lawyer Mr. Hawkins and the mental patient Renfield, into the oddity that is Knock.

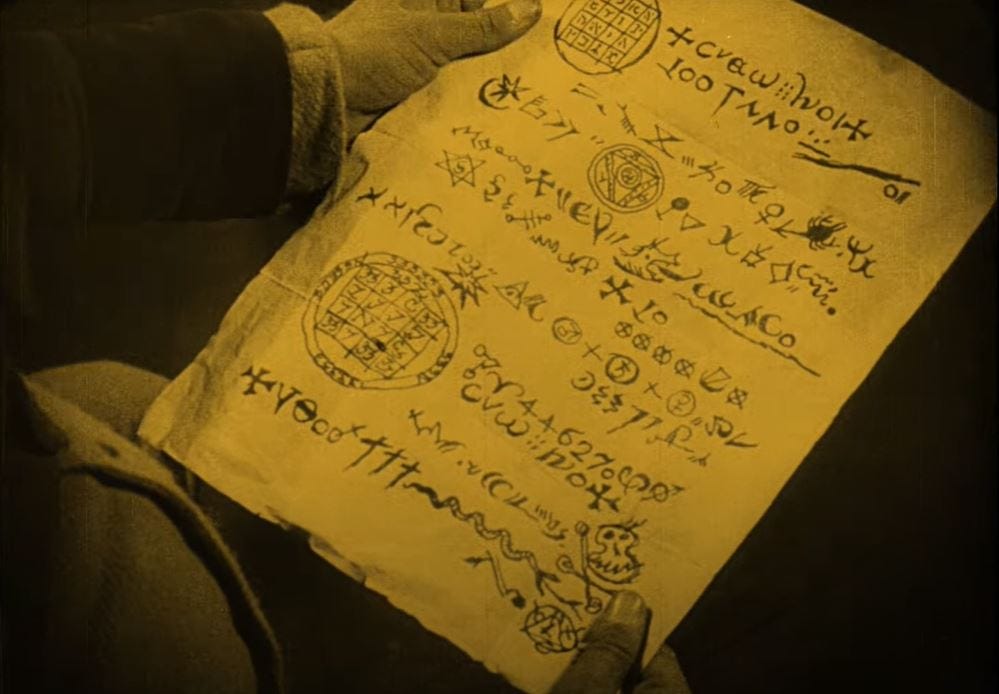

As soon as this little goblin creature receives a cryptic letter from a mysterious Transylvanian count (try and find all the esoteric symbols there, fun for the whole family!), he sends our young protagonist Hutter to serve as an estate agent, thought “it shall cost some effort, a bit of sweat, and perhaps… a little blood”.

Of course, Count Dracu- I mean Count Orlok, is also an elderly man, who preys upon the young. But we will get to him in a bit.

The only character who gets even close to Van Helsing’s role is Professor Bulwer, who does nothing for the entire duration of the film. He apparently knows Hutter, has a few comments on the Plague, and witnesses Ellen’s death. He gives no advice, no comforting words, no help against the present peril of Orlok; all he can do is walk away in sullen silence, leaving young Hutter to his grief.

So out of three aged characters, we have a traitor sending a bright youth to certain death, a vampire born of Belial’s seed who feeds on the blood of the young, and a generally useless savant who merely bears witness to the tragedy inflicted upon a young couple.

This, to me, looks like more than chance: the young bleed and die, while the old whimper, when they are not actively responsible for their demise.

You don’t have to look too far into it to think about the lost generation of World War One.

This war to end all wars shook the foundations of European society, namely by offsetting the male-to-female ratio in Europe (and changing marriage patterns in an indelible way), stoking the flames of communism in Russia and elsewhere, and destroying the fragile remnants of the old world by sending aristocrats and common men side by side to the slaughter.

Add in the understandable cynicism of a generation shaken by monstrosities beyond description (from shell shock to combat gas), and a rising contempt for traditional ideals and authority, and you get the seeds for a new society.

One like in Germany, where 13% of the active male population died over the span of four years. One that has lost 2 million lives only to lose territory, and become tributaries to their enemies. One that would be ready to embrace a new, changing world, leading them to the Weimar Republic, and that one other thing Germany will never live down. Even though, to some, it was a gas.

And speaking of Weimar…

“Hey, have you guys ever heard about sex?”

If you’ve ever read any web article concerning R.W. Murnau, you must have been told about a hundred times that he was extremely gay. Which I personally resent, as not all German people are homosexuals.

Some are just Austrian.

Anyway, for decades, Dracula has dragged in its wake a plethora of commentators whose raison d’être can be summed up thusly:

“How can I make this about sex?”

And yes, there are many clear innuendos in Stoker’s novel, showing a possible second reading of the story as a symbolic exploration of various facets of sex: from the fascination exerted by vampires over the minds of their victims, the penetration and exchange of fluids that occur when the vampire strikes, the possible double-meaning behind Lucy’s sleepwalking, Dracula’s bestial lust over Mina…

But people will legitimately come at you and seriously declare that Dracula was bisexual because he also bit men. And that Murnau’s alleged homosexuality is clearly shown by Orlok biting Hutter.

So, Dracula sucks off Harker, which means he’s a bisexual.

Which means… what? Is the Bloofer-Lady an Epstein client?

It should be obvious that many in academic circles have gleefully interchanged the first-level and second-lever readings of Stoker’s story. Now, the “hidden sexual double-meaning”, instead of offering a neat angle for analysis, is nothing more than a gimmick you can plop onto the story and say “this is what it’s about now, and nothing else”.

It’s willingly missing the forest for the trees. It’s seeing applicability, and calling it allegory.

It’s like saying the Book of the New Sun is nothing more than a metaphor, where Severian’s journey represents Gene Wolfe’s long winding path towards Catholicism: it’s probably in there to a degree, but you do yourself a disservice by dismissing every other possible meaning.

(Sidenote: if anybody does know what in the world the Book of the New Sun is supposed to be about, I would be eternally grateful. Thank you kindly.)

And speaking of heroes…

Ellen: she’s not your dad’s Mina Harker!

An article which I will not cite here stated that, contrary to Mina Harker’s “passive” role, Ellen Hutter takes on the monster herself, and becomes the true hero of the tale, sacrificing her life to save the town and the people she loves.

You may be wondering exactly when Mina Harker was ever “passive” in Stoker’s book: maybe when she was waiting for Johnathan to come back (ugh, of course the woman MUST wait for her future husband, how prude and patriarchal), except she takes care of Lucy in the meantime, saving her several times from Dracula’s grasp.

Or was it when she was compiling, filing, organizing and duplicating the entirety of all her husband’s and friends’ individual testimonies, to find out all they could about Dracula, which proved instrumental in his eventual defeat?

Or maybe we are meant to see her letting her mind commune with Dracula’s to locate and destroy him as passive, even though it was her idea?

Let’s face it: Mina Harker is indeed a damsel in distress. She needs people to look after her, help her, protect her. Which is why she is the beating heart of the rag-tag group of vampire hunters.

But her needing to be saved does not make her inactive or inferior, nor does it reduce her to a prop or a winning prize: to the contrary. It is her kindness, her virtue, but also her “man’s brain” and her strength of will even in the face of eternal death, which spur on Johnathan’s love, his friends’ admiration and Van Helsing’s fatherly affection.

Mina is amazing, and it’s no wonder the movies never do her justice.

Contrast this with Ellen, who is so depressed she feels sorry for flowers being plucked, and looks like she’s on the verge of dying of anorexia in the nearest Hot Topic.

Alright, to her credit, she is an entirely different character, and certainly the most interesting of the movie.

Her strange connection with her husband while sleeping gives her an eerie quality. She is a harbinger of doom, a wise woman who sees what others cannot. And this strange link is precisely what saves young Hutter from the clutches of Orlok.

Upon the first night Hutter spends in Orlok’s castle, the vampire sees a picture of Ellen. And later, as the creature walks up to a terrified Hutter to feed upon his blood, Ellen, way back in Wisborg, begins sleepwalking, and calling out for her husband. This seems to distract Orlok, who sulks away instead of finishing off his prey.

For the rest of the film, Orlok will be fascinated with Ellen, spying on her night and day, waiting for the moment where she will let her guard down and allow him to sink his teeth into her flesh.

And this is where Nosferatu shines: it becomes the harrowing tale of a young woman who sacrifices herself to save those she loves. She gives herself up to the monster, letting it feed upon her life, so that he lets himself be surprised by the dawn, and vanishes in the light of the living sun.

No wonder feminists may like this film: the woman’s main weapon is her body.

Instead of Mina’s purity of mind and body, which spurs on Dracula’s desire to defile her first before the rest of the group, Ellen uses her body to bait Orlok into bed in the hopes of destroying him.

Instead of the steadfast Mina, suffering the vampire’s stain with desperate patience with the aid of her knight-servants, Ellen is a desperate victim, who gives herself up to the devil to save her husband.

Maybe because, unlike Mina, she is alone, desperately alone. Even with her husband present.

There is something Faustian about her story: the desperate love, the symbolic damnation… All of which may serve a specific interpretation, which I will share with you in a minute.

But for now, let’s talk about Hutter for a bit.

Johnathan Harker: different name, same catastrophe

As some have said better, few characters are as maligned and hated in academic circles as Johnathan Harker.

In the novel, he shows a heroic disposition, but is far from fearless: indeed, in the very first chapters, he painfully relates his susceptibility to the terror inflicted by Dracula, and to the seductive glamour of his wives. But passing through this test thanks to his resourcefulness, he becomes the most determined of the group in eradicating the vampire’s evil, and the eventual death blow is rightfully his. At his core, Harker is a caring friend, and a devoted husband.

Now contrast this man with Nosferatu’s Thomas Hutter.

Much like Harker, Hutter, dismissing local superstitions, is sent to the Count’s castle, where he falls prey to the vampire, who leaves for his hometown while keeping him locked in. But as soon as he escapes from his prison, the two characters diverge entirely.

Because, although he doesn’t seem to be a bad bloke, Hutter has no drive.

As soon as he rejoins Ellen, he expresses relief, but does nothing to prevent Orlok’s arrival, or to hinder him in any way. He even asks Ellen not to read the book in which he himself had learned the nature of the vampire, and it is only by breaking that promise that Ellen finds how to defeat him for good.

There is no clearer way to show how useless he is than this: when Hutter is attacked by Orlok, Ellen calls for him in her sleep; but when the beast turns on her, Hutter keeps snoring the night away.

In fact, when Ellen finally lets Orlok in, she sends her husband away to fetch Professor Bulwer, so that she can be alone and keep the vampire by her side until sunrise.

Hutter is worse than useless: he is a hindrance to the vampire’s destruction.

And this has not escaped the deep analytical minds of our academics, who see in Hutter a deconstruction of masculinity, a representation of how useless men are against the threats women are set up against.

Either that or it’s about how much he’s gay.

Then again, this is the same sort of pseudo-academic lit-slop that will tell you with a straight face that Stoker’s story is obscurantist trash because people trust in God, but also a deconstruction of masculinity because a male character cries that one time.

So, we have discussed “men are bad”, “everyone is gay”, now it’s time to conclude with everybody’s favourite cut-and-paste literary lens: “it’s about being jewish”!

Orlok: “The Other” who may not be as alien as it seems

As I mentioned, Orlok seems to mostly prey on the young: outside of the shipmates of the Empusa, all his victims are in the flower of their age. One could see this as a continuation of the general theme of mistrust towards the old and powerful. And of course, older men taking sexual advantage over youths is far from uncommon, in reality or in folk tales.

People have tried to present this film as another example of the “fear of the Other”, by showing parallels between Orlok and the derogatory reputation of jews in medieval Europe: the blood-drinking, the wave of sickness, defiling young women…

Plus, there’s the nose, of course.

Murnau even adds a short segment on the population looking for a scapegoat, and choosing Knock as their victim, which one may liken to pogroms.

But I find this interpretation severely lacking:

1) Orlok is decidedly monstruous, and his features are hardly exaggeratedly semitic. The long tattered ears, stocky shoulders and lanky arms give the character a certain elfish look, or at least too fantastic to be representative of a specific ethnicity.

2) Knock’s little pogrom adventure is entirely deserved, as he has proven himself to be in the service of Orlok;

3) Orlok, in my opinion, symbolises something else. There is some evidence that he is indeed an “Other”, but something much more human, and much more terrifying.

As I said, Orlok’s weakness is his attraction to Ellen. He cannot rest until he has her. She is the reason he does not drain Hutter of his blood, she is the reason he goes to Wisborg, and she is the reason he eventually dies.

In a way, he is Hutter’s competitor, trying to snatch away his wife. But there is more.

When Ellen senses Hutter coming back to Wisborg, in another instance of sleepwalking, she reaches out for the heavens, saying: “I must go to him, he is calling!”

But this scene is intercutting with shots of the ship, now steered by Orlok, on its way to Wisborg.

Is Ellen sensing the coming of her husband, or of Orlok, whom she already may be aware of through her first “encounter” with him in her previous dream?

This may be a stretch, but I believe it is both.

After they return to Wisborg, neither Orlok nor Hutter meet one another. There is no final confrontation, even though they should be sworn enemies.

In fact, you never see them in the same room.

And what I mean by that is this: maybe Orlok, in a sense, is Hutter.

Think about it: Hutter returns from his journey at about the same time as Orlok: he arrives by day, while Orlok sneaks in by night. And Orlok only exerts his powers over Ellen when Hutter is asleep, or away.

Symbolically, I believe Orlok may be an exteriorization of Hutter’s shadow-self, or an embodiment of his raw sexual desire.

Hutter starts off his journey as a naive, happy-go-lucky boy: and in the end, while his conscious self is away, his shadow-self (Orlok) kills the object of its lust (Ellen), or symbolically, her innocence, leaving him to weep over his loss.

Thus, the beast was within the entire time. And because he did not confront it, he let it consume his beloved’s innocence, as well as his own. This idea of sexual awakening represented by death is also a typical analysis tool used in classic tales like The Erlking.

And this would give Professor Bulwer’s sadness ever more potent: by witnessing a young man grieving over his wife, the old man’s heart sinks back into heavy memories of love’s most cruel fangs.

There, that was my attempt at an academic’s analysis of Nosferatu from a non-retarded position.

And if you don’t like that interpretation, here’s another one:

Nosferatu is about an old homosexual who preys upon the youth, spreads deadly diseases, and can only be defeated by discovering you can also have sex with women.

… You know what? I take it back. Nosferatu is incredibly based.

Great article, man!